The Future of Indigenous Leadership in Canada’s Built Environment

The first time Trishtina Godoy-Contois, who goes by Trish, attended a conference for the national Quality in Canada’s Built Environment project, she was the only Indigenous student in the room.

She wasn’t studying architecture or urban planning. Instead, she’s a Métis woman pursuing a degree in political economics at Athabasca University who joined as a student rep.

The five-year project, supported by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC), began in 2022. It brings together 14 universities, 70 researchers, and 68 public and private organizations, including the Rick Hansen Foundation (RHF), to explore how Canada can redefine quality in the built environment through equity, social value, and sustainability. At its heart is a commitment to bring as many diverse voices as possible to the table.

When Trish arrived at her first conference in Montreal, she quickly realized the experience was unlike any she’d had before. “You can see that clash of worlds between research and on-reserve Indigenous youth. It’s a stark contrast of two different world views and life ways.”

Later, asked to speak on stage, Trish shared an analogy that struck a chord. Researchers may love presenting their expertise, she said, “but what if instead your subject matter expertise is, tell me about the day that you’re the hungriest, and you had no food, and it’s your sad story. How willing are you going to be to do that?” That honesty, she added, “moved people… just interrupting those moments and giving some perspective.”

A Mission Begins

Looking around the room at the conference, Trish wondered at the lack of Indigenous representation.

“I worked as an employment counselor for the Métis Nation of Alberta for a number of years before I went back to school. And I know that Indigenous students exist.”

That realization became a mission: to see each of the universities involved in the SSHRC project bring on at least one Indigenous architecture student. With early support from the Royal Architectural Institute of Canada, SSA Studio, and The Rick Hansen Foundation, the project was able to cover travel and conference costs for Indigenous students.

Out of this effort grew the partnership on quality Emerging Indigenous Leaders group in the spring of 2025. “Now we have a consistent group,” Trish said. “It’s only about five students currently, but they’re all architectural students, and they’re all actively engaged within their schools.”

The numbers, however, remain stark. At the University of Calgary, she noted, “there were only two with an undergrad and masters, one of them graduated, and he’s still a part of our group. So that means there’s currently only one student… that’s a pretty wild thought out of a school that has several hundred seats available.”

Across the country, Trish believes more needs to be done to create opportunities for Indigenous students in architecture, a gap she is determined to help close. Currently, she added, there are under 30 working in the field.

Gaps and Pathways

The challenges Indigenous students face in research and design are often both structural and cultural. “Too often, the path requires students to conform or assimilate to some degree,” Trish explained. “That creates a gap between what the on-the-ground research should look like if it were community-based, versus what it is in academia.”

So, what would an Indigenous-led architectural pathway look like?

“It would be practical, it would be holistic, and it would navigate a learner through experientially,” she said. That means training not just in design, but also in the bureaucratic realities of housing applications. “If you’re going to be working on reserve and trying to address housing through design, then you need to be informed about what Indigenous Services Canada expects in those housing applications.”

She also envisions stackable credentials. “Getting through a one-year certificate is way more approachable and something that could stack towards an undergraduate degree, but immediately would release you into doing engagement consultation work to bridge that communication divide between architects, planners, and community.”

The barriers to integrating Indigenous perspectives into architecture, Trish noted, often echo those faced in accessibility. She recalled a conversation with a practicing architect who had developed a disability. When clients wanted to cut costs, “she has to still be the one in that system that works with a client who says, ‘let’s cut costs. And we can cut costs by removing the ramp.’”

“It’s the same dynamic,” Trish said, pointing to how marginalized communities are often treated as negotiable. “It’s a quality versus cost factor.”

A Glimpse of the Future

What happens when Indigenous leadership is centred, not consulted as an afterthought? Trish is candid: “It’s hard to say what it looks like, because I haven’t seen it done.”

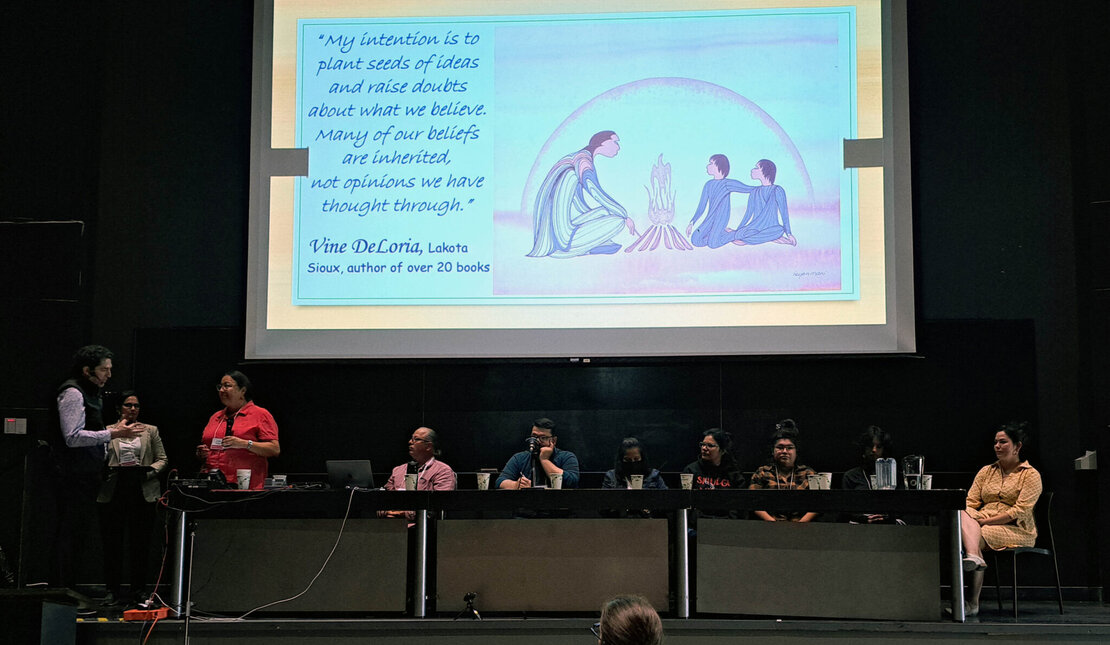

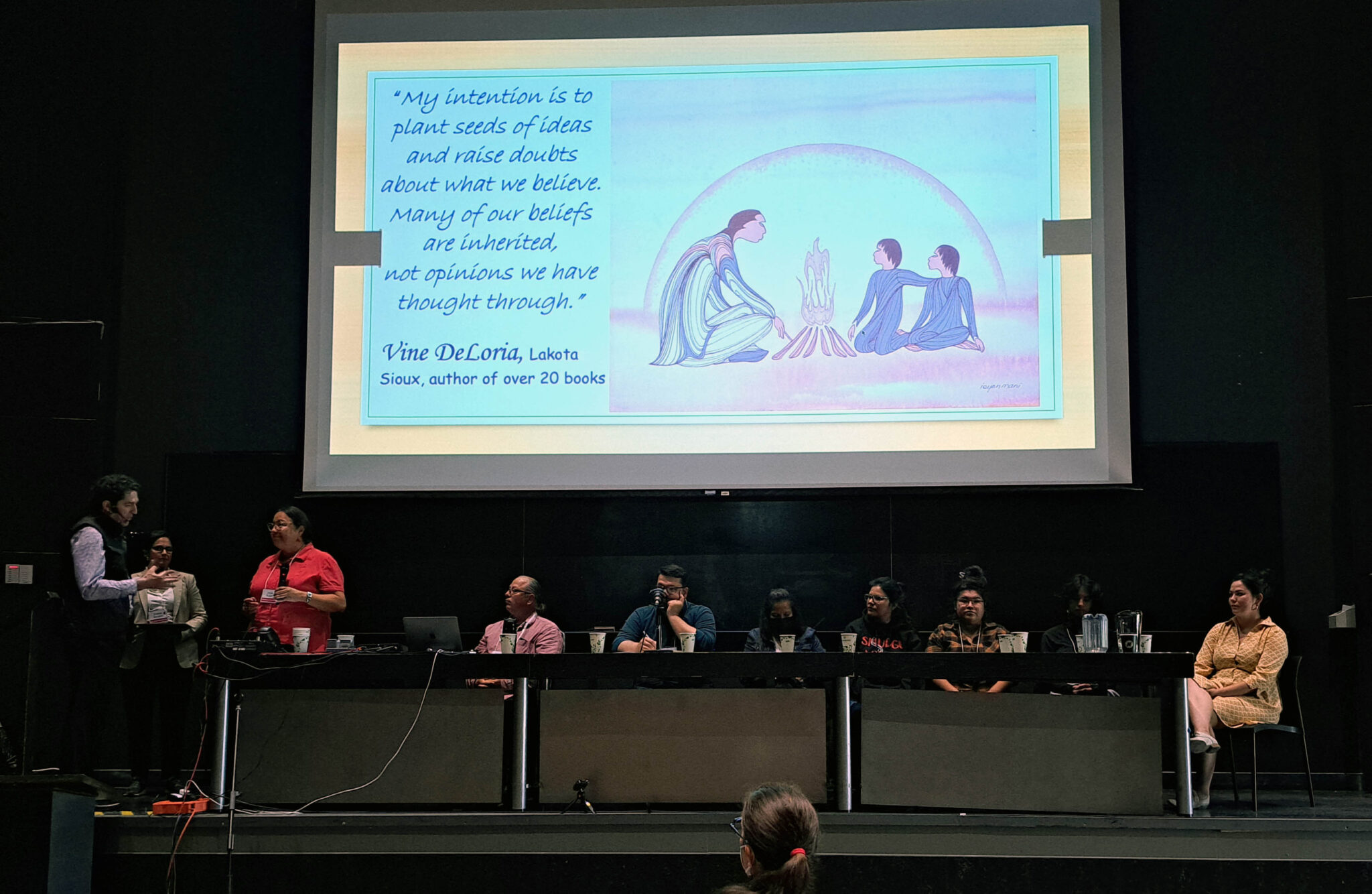

But the partnership on quality in the Emerging Indigenous Leaders group has offered a glimpse. The group co-created a set of national actions and a governance roadmap. During an impromptu circle, Chief Darryl Wastesicoot put out a call to redesign how education, housing, and leadership intersect to drive quality, of which the Fire Keepers Circle was born – a national governance model aimed at embedding Indigenous governance within design education and infrastructure policy.

“People were shocked at the quality of the work that we were able to deliver in the short time period we were given… we just got down to it… and we did that voluntarily,” Trish said.

The effect, she believes, is transformative. “You come with a complete thought that someone else is not even thinking about. So, it just enriches the experience.”

For Trish, work on the SSHRC project is both personal and collective. She described it as “by far, my favourite” and called working with other community partners, such as The Rick Hansen Foundation, “a real pleasure.” Most of all, as an advocate, strategist, and the Indigenous Coordinator for the project, she sees momentum. “It’d be amazing if we could get the group to expand even more… how do we leverage this into us working together?”

As she looks to the future, Trish hopes the lessons of the project will carry forward: including the voices of Indigenous peoples, people with disabilities, and other underrepresented communities in architecture should one day be the norm, not the exception. The SSHRC partnership on quality experiment is one step toward making that a reality.

For more information on the project, visit https://livingatlasofquality.ca/

Or to share your experience of a place to raise the bar of quality in Canada, visit the open access database at https://archiqualidata.ca/en?filters=